The question regarding the possibility of prioritizing pragmatism and rationality over ideology in determining foreign policy yields an answer that does not remain constant over time. Theorizing on this subject has accompanied historical processes, as well as political figures and regimes that have shaped the course of States and societies.

To ground this in the present, political science—specifically international relations—has developed a discipline called Foreign Policy Analysis, through which international decision-makers are analysed but also equipped with coherent mechanisms to determine the foreign policy of the State they represent.

To better understand this, Valerie M. Hudson describes the contribution of Foreign Policy Analysis as a scientific discipline:

Examining the history, conceptual breadth, and recent trends in the study of foreign policy, it becomes clear that this subfield provides perhaps the best conceptual connection to the empirical ground upon which all International Relations theories are based. Foreign Policy Analysis is characterized by its focus on a specific actor, grounded in the argument that everything occurring between nations is based on human decision-makers acting individually or in groups. Foreign Policy Analysis offers significant contributions to international relations in its theoretical, substantive, and methodological perspectives; it is situated at the intersection of all social sciences and fields encompassing public policy, provided they have a direct link to international relations. A renewed emphasis on actor-specific theory will allow international relations to forcefully reclaim the ability to manifest human agency, accounting for its constant change, creativity, dependency, and meaning. (Hudson 2005)

To answer the question about the possibility of prioritizing pragmatism and rationality over ideology in foreign policy determination, it is necessary to define the concepts that construct pragmatism, rationality, and ideology. Only by breaking down these three concepts can one determine if a pragmatic and rational foreign policy is possible and what conditions are required to achieve it.

Rationality in Foreign Policy Generation

Understanding that foreign policy generators are individuals, cognition plays a central role in determining the capacity to generate rational foreign policy. So-called cognitive shortcuts can limit information processing, as determined by Alex L. George in his 1969 study titled “Operational Code,” which defined cognitive shortcuts as the pillar of rationalist and constructivist theories explaining the foreign policy decision-making process (Levy 2003).

Within the rationalist–constructivist debate on rationality, the concept is disputed between the need to satisfy or maximize utility given an individual’s interests (Rosati 2000; Carlsnaes 1992). Before identifying the individual as the central actor, the State—an abstract entity—was understood as the decision-maker. Under this precept, maximizing utility implied making decisions based on holding one hundred percent of the information. After understanding that decisions are made by individuals rather than States or institutions, scholars realized the impossibility of decision-making with perfect information. The concept of aiming for the most satisfactory result became the rational way to make decisions, and the definition of satisfaction constituted a new dilemma in theorizing (Wight 2002).

Furthermore, understanding the individual as a decision-maker means emotions play an important role, giving rationality a new meaning. George E. Marcus (2003) traces this back to Plato, passing through Descartes, Kant, Hobbes, and Hume, who in various ways separated emotion from reason as if they were antagonistic processes. Marcus explains how interests and feelings were initially conceived as distinct categories. Emotion was associated with passion, and interest with rationality. The current perception of emotion’s effect on reason is that emotion will distort rationality. However, neuroscience discovered that through emotion, one acquires the capacity to externalize behavior. Without the capacity for emotion, individuals cannot externalize the behavior recommended by their reasoning (Marcus 2003). It is impossible to eliminate emotions from behavior. Therefore, without emotions, rational action is impossible. Thus, rational decision-making is limited to the individual’s ability to channel their emotions, experience, and knowledge (information).

Ideology and the Ideologization of Foreign Policy

Broadly speaking, doctrines are a selection of beliefs that determine the actions of decision-makers. Beliefs put together in an organized framework are known as ideologies (Goldstein & Keohane). Ideologies are a set of ideas that determine decision-makers’ goals and justify individuals’ decisions and foreign policy by providing moral and ethical justifications for action and decision-making (Ibid).

The first use of the term ideology is recorded in the 18th century. Kellner mentions that ideology was used to ontologically describe the nature and social function of ideas in seeking to provide rational foundations for human knowledge. The concept of ideology developed from the attack on European feudal power as a product of the bourgeois revolutionary movement (Kellner 1978).

By the 19th century, an ideology’s values preached its moral character (Scarbrough 1984). Currently, ideology is conceived as the sole factor in foreign policy development contributing to shaping decision-makers’ criteria and their image of political life. Andrew Heyworth explains that political ideas help forge the political system in its essence (Heyworth 1998).

Carlsnaes argues that a State’s foreign policy is essentially an expression of its peculiar ideology (Carlsnaes 1986). This concept is plausible if one understands that decision-makers and foreign policy generators interpret and analyze information according to their beliefs and perceptions. In other words, ideology constitutes a filter through which information is processed and classified relative to the image projected by the individual’s ideology, which can translate into massive and common political language (Ibid). In this regard, Holsti identifies ideology as messages and patterns from the external environment that are given meaning or interpreted within the framework of categories, predictions, and definitions provided by the doctrines composing the ideology (Holsti 1995).

However, it must be taken into account that in many cases, decision-makers and foreign policy generators are not governed by their individual values or ideologies but by specific interests or priorities. Jervis argues that foreign policy generators tend to alter their original beliefs and establish new ones to accumulate more justifications backing certain decisions (Jervis 1976).

Going even further, some argue that ideologies are merely a tool to disguise the real nature behind the political actions of some individuals, who deliberately camouflage themselves behind the veil of political ideology to pursue interests of a different nature (Morgenthau 1993). This shows that following the thread of ideology, whatever it may be, does not lead to identifying the underlying motives driving decision-makers. Discovering that motivation could only be achieved through deep and exhaustive analysis of the objectives pursued by the individual in question (Ibid). Consequently, one could argue that the pursuit of power underlies ideologies, and involvement in the race for power becomes morally and psychologically acceptable, both for decision-makers and the population, if an ideology backs this action. Heywood (1998) emphasizes that ideology is a socially accepted idea used to legitimize a political system or regime.

The nation that would dispense with ideologies and frankly declare that it wishes to accumulate power, while simultaneously opposing similar aspirations of other nations, would find itself at a great disadvantage in the race for power. (Morgenthau 1993)

This perspective shows that ideology serves power accumulation and prioritizes national rather than ideological interests in most cases.

Therefore, State leaders, when conducting foreign policy, should adopt a stance oriented toward defending and prioritizing State interests despite the ideological principles and values promoted by their Government. This is where pragmatism is achieved. Examples of ideological discourses not applied in foreign policy are numerous: Iran’s relationship with Russia despite not being an Islamic State; Venezuela selling oil to its declared number one enemy, the United States of America; the European Union’s relationship with Turkey maintaining commercial relations for oil and gas supply despite ideological differences. There are many examples of political leaders who managed to develop a pragmatic foreign policy despite ideological discourse.

Pragmatism and Realpolitik

Pragmatism is defined by Henry Kissinger as a bureaucratic decision-making system, a response to situations without reacting emotionally to them. Problems, under this understanding, are segmented into elements treated by experts, and recommendations are made according to the tradition and customs of the bureaucratic system (Kesseiri 2005).

In foreign policy, pragmatism allows State leaders to achieve sensible and practical results, thus avoiding the stumbling blocks of ideological stubbornness.

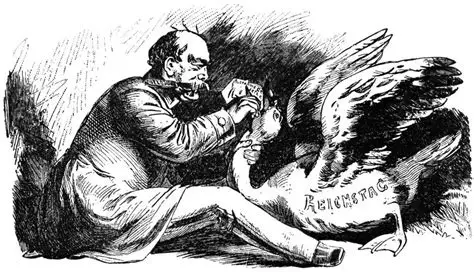

The term “Realpolitik” applies as a synonym for “power politics” and is understood as the realistic approach to foreign policy, resonating in political science from Machiavelli, through Otto von Bismarck, to post-war diplomats and academics like George Kennan and Henry Kissinger. The term was first recorded in the 19th century by German August Ludwig von Rauch, for whom “Realpolitik” referred not so much to philosophy as to the mechanism for overcoming the complications of a hostile and constantly conflicting Europe thanks to the forces of liberalism and nationalism that ended up forging the modern Nation-State.

Conclusions

Foreign policy admits the ideologization of political life for justification, while prioritizing and placing State interests first in its execution. This means the balance between ideology and pragmatism is real and must be assumed as a priority by decision-makers and State leaders.

Rationality in decision-making is relative due to the involvement of factors such as emotions, information quality, and the decision-maker’s experience.

It is therefore possible to achieve a coherent and pragmatic approach to foreign policy and international relations; however, one must know how to balance and conduct it.

Currently, theoretical currents regarding the “end of ideology” and the non-acceptance of framing foreign policy within any ideology mark the debate around the question of the possibility of employing pragmatism and rationality over ideology in foreign policy determination.

In the first case, the “end of ideology” is conceptualized around developed countries, where ideologies moved to a second tier to prioritize pragmatic policies without the need to camouflage or justify political decisions with ideologies. Moreover, left and right parties coincide on issues such as the need to narrow the economic and social inequality gap or the need to protect the environment.

Developing countries remain ideologized in their foreign and domestic policy because it is argued they have not yet reached the maturity to pragmatize their politics.

On the other hand, there is the argument that in no state in the world is it necessary to maintain an ideology to justify foreign policy decisions. Modernity and technological advancement provide conditions to inform the population, as well as political leaders, about the need to approach foreign policy pragmatically.

When generating and implementing foreign policy from a developing country like Bolivia, the lack of adequate institutional structures for foreign policy formulation stands out, making ideologization easily overshadow pragmatism.

References

Hudson, V. M. (2005), Foreign Policy Analysis: Actor-Specific Theory and the Ground of International Relations. Foreign Policy Analysis, 1: 1–30.

Levy, Jack S. (2003) Political Psychology and Foreign Policy. In Sears, D., Huddy, Leonie, & Jervis, Robert. (Ed.) (2003) Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 253 – 284). Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Rosati, J. (2000). The Power of Human Cognition in the Study of World Politics. International Studies Review, 2(3), 45-75.

Carlsnaes, W. (1992). The Agency-Structure Problem in Foreign Policy Analysis. International Studies Quarterly, 36(3), 245-270.

Walter Carlsnaes, Ideology and Foreign Policy: Problems of Comparative Conceptualization

(Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986), 138.

White, C., (2002) Philosophy of Social Science and International Relations. In Carlsnaes, W., Risse-Kappen, Thomas, & Simmons, Beth A. (Ed.) (2002). Handbook of international relations (pp 23-51). London, Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications.

Marcus, G. E., (2003) The Psychology of Emotion and Politics. In Sears, D., Huddy, Leonie, & Jervis, Robert. (Ed.) (2003) Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 182-221). Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Judith Goldstein and Robert O. Keohane, “Ideas and Foreign Policy: An Analytical

Framework,” in Judith Goldstein and Robert O. Keohane (eds.), Ideas and Foreign Policy:

Beliefs, Institutions, and Political Change (Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press, 1993), 16.

D Kellner, “Ideology, Marxism and Advanced Capitalism,” Social Review 8, (1978), 39.

Elinor Scarbrough, Political Ideology and Voting: An Exploratory Study (Oxford: Clarendon

Press, 1984), 28.

Andrew Heywood, Political Ideologies: An Introduction, Second Edition (London: Macmillan

Press, 1998),4.

Karl J Holsti, International Politics: A Framework for Analysis, Seventh Edition (: Prentice

Hall International, 1995), 271.

Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton, New Jersey:

Princeton University Press, 1976), 137.

Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, Brief

Edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1993), 126.

Bew, J. (2016). Realpolitik: A history. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kesseiri, Radia (2005) Ideologised foreign policy and the pragmatic rationale : the case of Algeria under Houari Boumedienne, 1965-1978 /